James Deakin slams LTO over son’s reckless driving case, is this trial by publicity?

Margret Dianne Fermin • Ipinost noong 2026-01-09 10:32:03

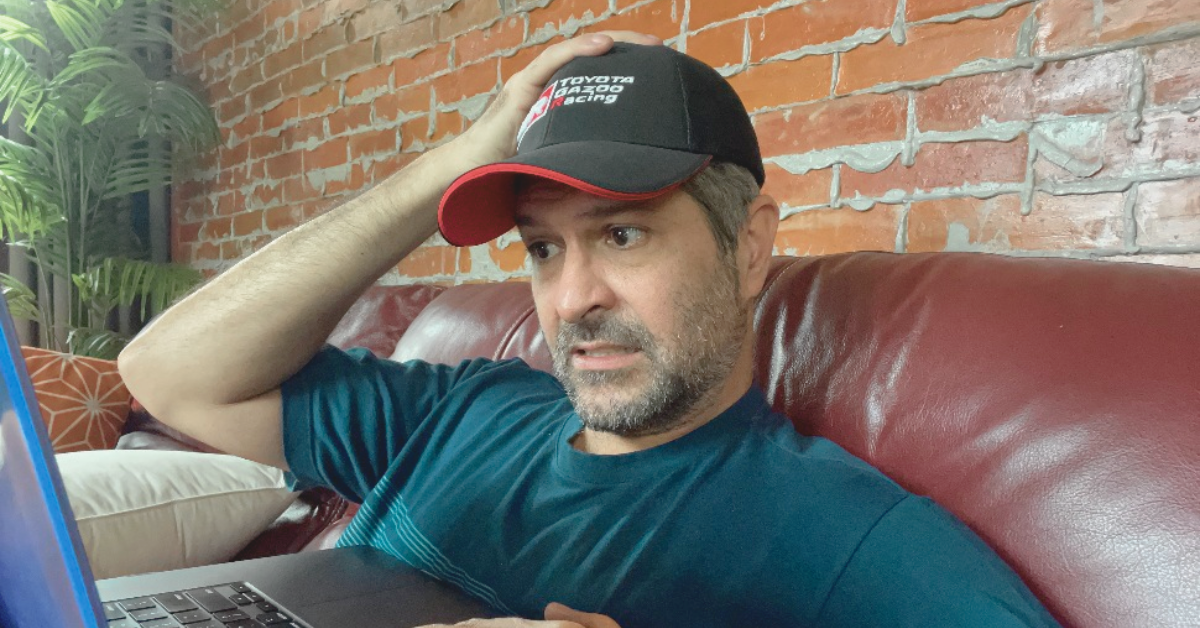

MANILA, January 8, 2026 — Motoring journalist James Deakin has criticized the Land Transportation Office (LTO) for what he calls “trial by publicity” and a contradictory definition of reckless driving, after the agency revisited his son’s traffic violation in a press conference.

Deakin’s son was cited for a traffic violation on the Skyway in December 2025, a charge the family never disputed. “He took the ticket, didn’t contest it, and paid the fine—effectively closing the case. It’s done and dusted. The ink has dried. Elvis has left the building,” Deakin wrote in his January 8 post.

Yet, during a January 7 briefing, the LTO presented the violation as new information and added another charge: that the vehicle driven was unregistered. Deakin said this amounted to trial by publicity, noting that the agency chose to broadcast evidence on national television rather than provide it directly to the accused.

Deadline, Paperwork, and Double Standards

Deakin stressed that the real issue was not the violation itself but the bureaucratic hurdles that followed. He pointed to the 15‑day deadline for contesting charges, which included eight or nine days when the LTO was closed, and the demand for printed documents not listed in the Citizens Charter.

He questioned why citizens are bound by calendar days while the agency operates on working days, calling it a clear double standard. “When the public wait months and years for plates or plastic cards, it’s just brushed off as an administrative issue. Yet when we miss the deadline, even when you’re closed, it’s automatic suspension and public shaming,” he argued.

Reckless Driving: Statutory vs. Administrative Definition

Central to Deakin’s criticism is the LTO’s administrative interpretation of “reckless driving.” Under Republic Act No. 4136, Section 48 (Land Transportation and Traffic Code), reckless driving is defined as:

“Driving any vehicle on any public highway recklessly, without reasonable caution, considering the width, traffic, visibility, and other conditions of the road, and in a manner so as to endanger the safety of persons or property.”

Deakin argues that this statutory definition requires proof that a driver acted without reasonable caution and in a way that endangered safety. A simple traffic violation, such as crossing a double yellow line, may be punishable, but it does not automatically meet the threshold for reckless driving under the law.

“All I wanted was clarification and legal advice so I could understand what actually constitutes reckless driving. That’s it,” Deakin explained, noting that his initial query to a colleague was met with irrelevant remarks about a “no padrino policy.”

Call for Accountability

While acknowledging responsibility for not double‑checking the loaner vehicle’s registration, Deakin questioned why the traffic enforcer failed to cite it at the time of violation and why it passed through multiple LTO layers without detection.

He concluded by urging the agency to stop deflecting and address the systemic issues:

- Why do calendar days apply to citizens but working days apply to you?

- Why demand printed documents not in the Citizens Charter?

- Why does your definition of “reckless driving” contradict the statutory standard?

- Why show evidence to media before showing it to the accused?

“I’ve already admitted where both my son and I fell short and we took the penalty on the chin; so let’s see if you will do the same and drop the double standards,” Deakin said.

If This Can Happen to Them, It Can Happen to Anyone

This issue is bigger than one family or one traffic stop. When a settled violation is reopened in public, deadlines feel elastic for agencies, and definitions shift midstream; ordinary motorists should pay attention.

Most drivers do not have a platform. They cannot question agencies on equal footing or demand legal clarity when rules seem to change. They face the same calendar-day deadlines, the same document demands, and the same risk of penalties without explanation. When enforcement turns performative, power tilts sharply away from the public.

Rules must be predictable. Due process must be quiet, fair, and consistent. Evidence should go to the accused before it goes to the cameras. Laws should mean what statutes say, not what press briefings suggest. And deadlines should apply equally to both sides of the counter.

Road safety depends on trust. Trust depends on systems that correct mistakes without humiliation and enforce standards without spectacle.

If those with visibility can be put through public scrutiny after compliance, what protection do everyday motorists really have?